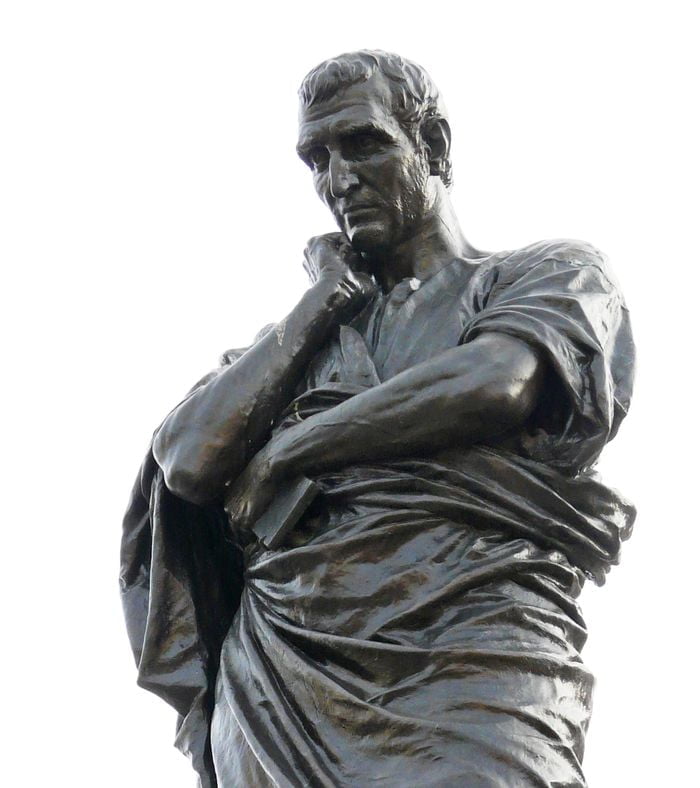

Shimazaki Toson (1871-1943)

Shimazaki Toson began writing as a poet of the new era, but after the Russo-Japanese war, he turned to naturalistic fiction. He wrote novels derived more or less directly from Europe, but in his short stories he remained more genuinely Japanese. “Intimacy with nature,” says the translator, “and intimacy with life,” are felt throughout his little stories.

This story, translated by Torao Taketomo, is reprinted from the volume, Paulownia, copyright, 1918, by Duffield & Go., New York, by permission of the publisher.

A Domestic Animal

Her first misfortune was at her birth; she came into the world with short gray hair, overhanging ears, and fox-like eyes. Every animal which is called by favor domestic has a certain quality which attracts to itself the friendly feeling of man. But she did not have it. Nothing in her countenance seemed to be favored by man. She was entirely lacking in the usual qualifications of a domestic animal. Naturally she was deserted.

However, she was also a dog, an animal which cannot live by itself. She could not leave the hereditary habitat to be fed by people and then go back to the wild native place of her remote ancestors. She began to search after a suitable human house.

This troublesome being strayed to the estate of Kin san, a planter, when the building of the new wood-roofed rent house was just finished. The house was built along the village road of Okubo, located in such a manner as to enable one to go to the main street through the back yard. The floor was high and the ground was dry. Moreover, there was a narrow, dark, unoccupied space at the foot of the fence between this house and the next, so that she could promptly hide herself in emergency. She lost no time in occupying this underground refuge.

The urgent necessity was to get the food. There were two more rent houses on this estate, which made four with the farm-like main house where Kin san`s family lived. These houses stood each against the other and trees with graceful branches were between them. Her sharp nose taught her first the direction toward the kitchen.

As she was hungry, there was no time for choice. Peeled skins of fruits, cold, evil-smelling soup, corrupt remnants of dishes—she ate everything she could get. If these were not enough to satisfy her, she smelt around even the dust heap, and hunted as far as she could hunt. Some dirty socks were soaked in the wash-tub beside the well. Gladly, she drank the water from the tub.

Read More about The Prodigal Son