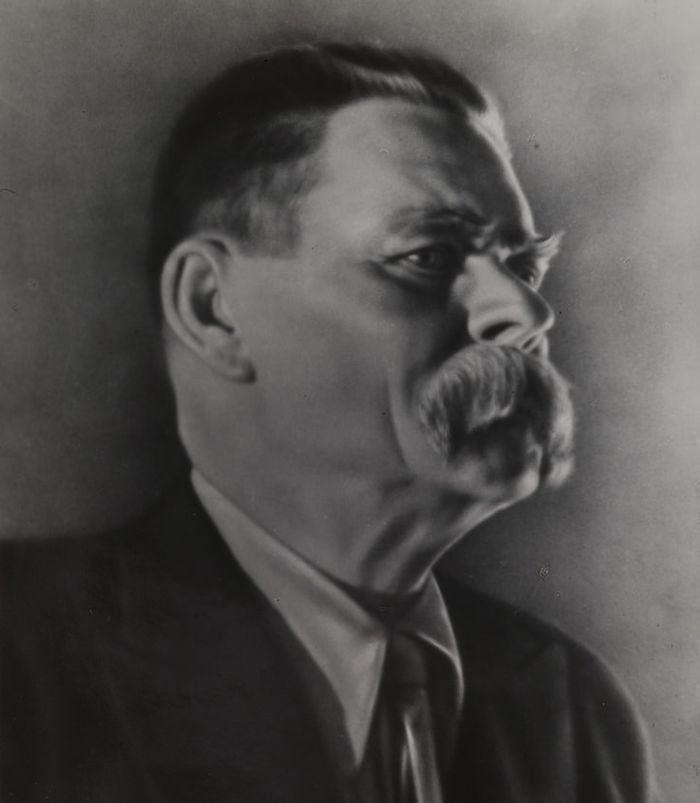

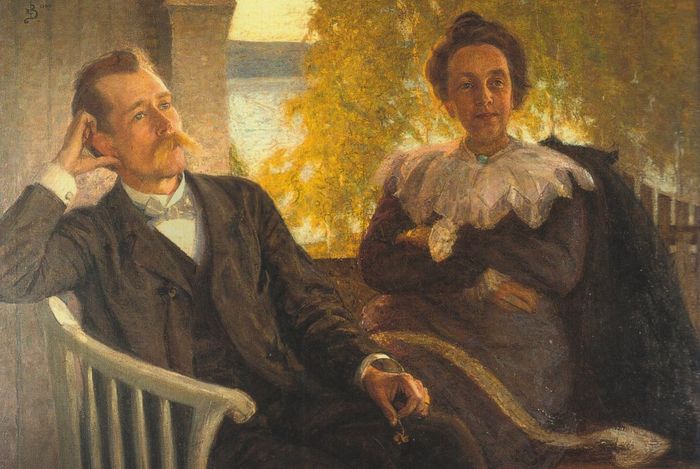

Falcon – Per Hallstrom (1866—1960)

Per Hallstrom travelled widely. He was for some time an ana-lytical chemist in Chicago, and his work shows traces of foreign influence. He brought the art of writing stories to a high point of perfection and is one of the few Scandinavian masters of that form.

The Falcon is translated by Herbert G. Wright. It first appeared in the American-Scandinavian Review, October, 1920, and is reprinted by permission of the editor.

The Falcon

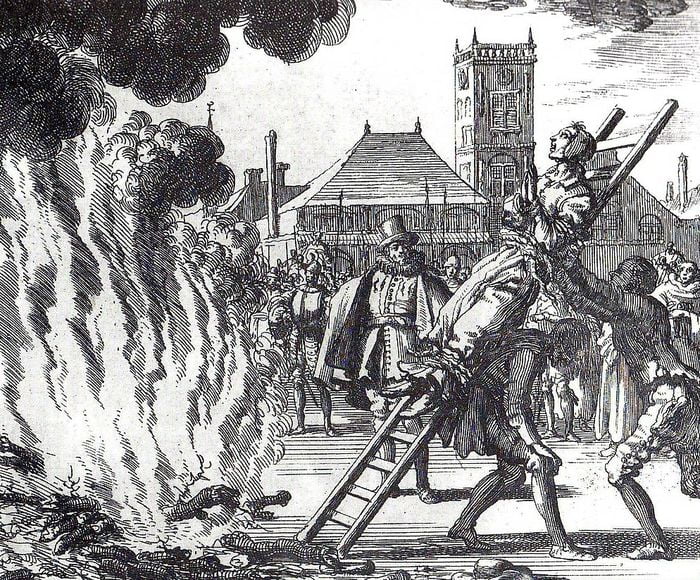

Sir Enguerrand rode out hunting every day, and generally with his red, gold-embroidered glove on, for only the( flight of the Iceland falcon with his tinkling bells could awaken music within him and make him breathe the keen, light morning air with joy, as he were drinking an animating wine. One day the falcon had driven a heron bleeding into a marsh behind a copse, where the huntsman found it and broke its neck, but the falcon himself was gone.

Whether he had been attracted by a fresh prey, or, had shunned the brown water, or by some caprice had let himself be thrown aloft and carried away by the wind—in vain they searched; in vain they called caressing names; in vain they let the sound of the horn beat against every height. Sir En- guerrand struck the trembling mouth of the head falconer with his glove until the blood flowed, and rode home at a gallop over the tufts of grass, his lips closed still more firmly and his eyelids lowered still more gloomily over the listless pupils—and the falcon was not found.

But Renaud found him, caught by the thong round his foot in a briarbush, motionless, awaiting death from starvation with a firm grip of the branch, one wing hanging, the other raised defiantly, the narrow head stretched forward threateningly with eyes fixed and beak keen— beautiful he was amidst the blood-red berries. Renaud’s hand trembled with eagerness as he disentangled the thong from the thorns, as the bells jingled about his fingers on the ring with the mark of Sir Enguerrand. He called aloud with joy, when the sharp claws cut into his sinewy arm, and he was his, the falcon with the broadest breast and the longest wings and the proudest eyes of burning gold.

He was all the more his, since he would never be able to show him to anyone, for he knew that rigorous laws protected the sport of the knights. In the forest he would build a cage for him; early in the morning he would steal thither, before the bird had shaken off the cold; over the fields they would go together, sweeping with their gaze the white upper regions; they would become fond of each other, as they let the sunshine rise and fall over their heads and the wind carry off their silent thoughts, and the falcon would never miss his red glove nor the restraint of his pearl-bedecked hood.