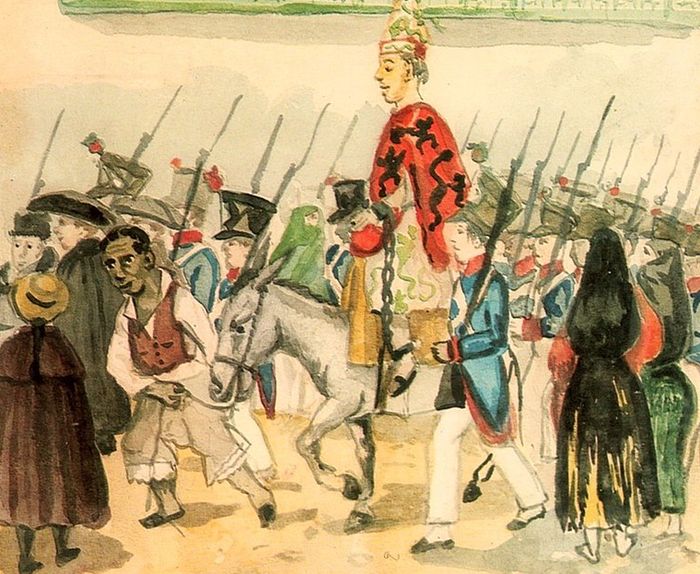

Round the churchyard a multitude gathered in front of a long low green farmhouse. The proprietor wept bitterly as he stood in his door-way. He was a fat, jolly-looking man, and happened to arouse the compassion of a few soldiers who sat near the wall in the sunlight, patting a dog. The soldier who was taking off his child made gestures as if to convey the meaning, “What can I do? I`m not to blame!”One peasant who was being pursued leaped into a boat near the stone bridge, and, with his wife and children, rowed quickly across that part of the pond that was not frozen. The Spaniards, who dared not follow, walked angrily among the reeds by the shore. They climbed into the willows along the bankside, trying to reach the boat with their lances. Unable to do so, they continued to threaten the fugitives, who drifted out over the dark water.The orchard was still thronged with people: it was there, in the pres-ence of the white-bearded commanding officer, that most of the children were being murdered. The children who were over two and could just walk, stood together eating bread and jam, staring in wide-eyed wonder at the massacre of their helpless playmates, or gathered round the village fool, who was playing his flute.All at once there was a concerted movement in the village, and the peasants made off in the direction of the castle that stood on rising ground at the far end of the street. They had caught sight of their lord on the battlements, watching the massacre. Men and women, young and old, extended their hands toward him in supplication as he stood there in his velvet cloak and golden cap like a king in Heaven.But he only raised his hands and shrugged his shoulders to show that he was ownerless, while the people supplicated him in growing despair, neeling with heads bared in the snow, and crying piteously. He turned slowly back into his tower. Their last hope had vanished.When all the children had been killed, the weary soldiers wiped their swords on the grass and ate their supper among the pear-trees, then mounting in pairs, they rode out of Nazareth across the bridge over which they had come.The setting sun turned the wood into a flaming mass, dyeing the vil-lage a blood red. Utterly exhausted, the curd threw himself down in the snow before the church, his servant standing at his side. They both looked out into the street and the orchard, which were filled with easants dressed in their Sunday clothes.Before the entrances of many ouses were parents holding the bodies of children on their knees, still full of blank amazement, lamenting over their grievous tragedy. Others wept over their little ones where they had perished, by the side of a cask, under a wheelbarrow, or by the pond. Others again carried off their dead in silence. Some set to washing benches, chairs, tables, bloody underclothes, or picking up the cradles mat had been hurled into the street.

Stopping by Grief- Stricken

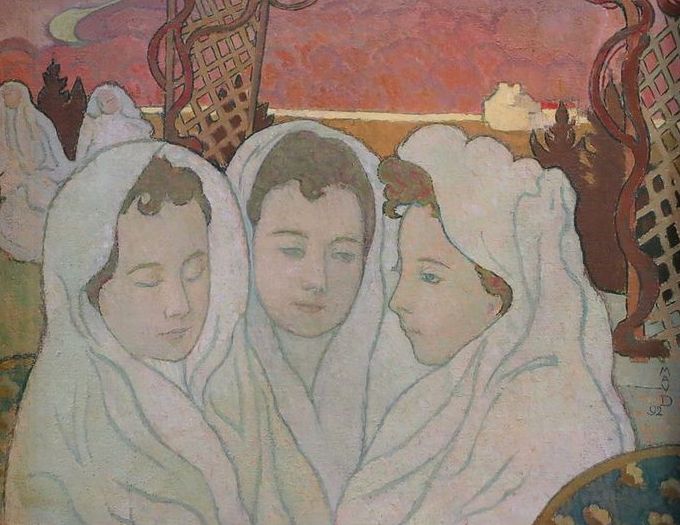

Many mothers sat bewailing their children under the trees, having recognized them by their woolen dresses. Those who had had no children wandered through the square, stopping by grief- stricken mothers, who sobbed and moaned. The men, who had stopped crying, doggedly pursued their strayed beasts to the accompaniment of the barking of dogs; others silently set to work mending their broken windows and damaged roofs.As the moon quietly rose through the tranquil sky, a sleepy silence fell upon the village, where at last the shadow of no living thing stirred.

Read More about The Massacre of the Innocents part 4